Home > Jazz / Blues

07/14/2015

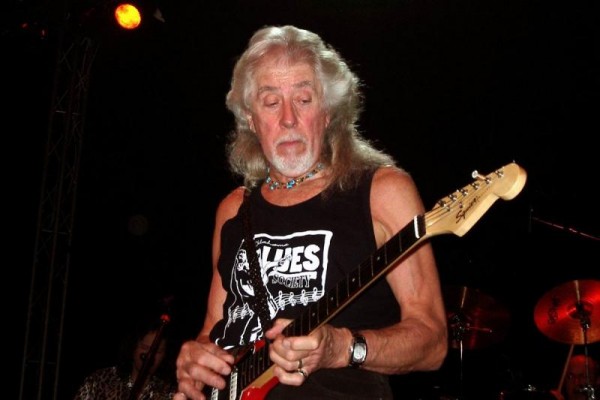

John Mayall: A Portrait of the Blues

BY NATHAN RIZZO // Responsible for launching some of music's most iconic careers, Mayall continues to entertain the masses at the age of 81

Most often credited with the wider revelation of Eric Clapton, John Mayall’s impact on rock and roll is inestimable. A prolific singer, instrumentalist and bandleader, Mayall would team with Clapton to record 1966’s Bluesbreakers with Eric Clapton, a landmark album of standards and Mayall originals that would propel Clapton and his searing blues-rock stylism to stardom in England and abroad. Departing soon thereafter to form Cream with bassist and Bluesbreakers alumnus Jack Bruce, Clapton’s position – and others – would be filled by a remarkable succession of burgeoning talent, including guitarist Mick Taylor, who would later join the Rolling Stones, and the original Fleetwood Mac lineup of guitarist Peter Green, bassist John McVie, and drummer Mick Fleetwood.

While broadly renowned for his affiliations with the likes of Clapton and Taylor, and the work born of those partnerships, Mayall has never appeared content to trade on past glory or the notoriety of former collaborators whose fame would ultimately eclipse his own. Seemingly inexhaustible, Mayall has maintained an unceasing schedule of recording and touring for nearly 50 years. Now 81, Mayall is preparing to release Find a Way to Care, his latest effort showcasing a longtime backing band of guitarist Rocky Athas, bassist Greg Rzab, and drummer Jay Davenport.

Interviewed in advance of his Wednesday, July 15 performance at Portland’s Aladdin Theater(Doors 7:00 PM; Show 8:00 PM; Tickets $30) Mayall recalls his early interest in the blues and offers his thoughts on Mick Taylor’s musical character and the stunted trajectory of Taylor’s solo career. Mayall also relates memories of Jimi Hendrix before touching on his relationship to the broader narrative of career, the timeless qualities of the blues, and a recently unearthed recording of a 1967 Bluesbreakers concert featuring Green, McVie, and Fleetwood – all of whom would depart en masse to form Fleetwood Mac within mere months of the performance.

You’ve said you first got into the blues because your father had a great record collection with a lot of blues and jazz. Do you have specific memories of what was always on in your house growing up?

Well, he didn’t really have very much blues stuff – I came into that on my own. But the nearest I could get to blues music was probably stuff by the Mills Brothers and maybe Eddie Lang. Those are two that come to mind – Spirits of Rhythm, also.

But there were very few things of a blues nature. It was more jazz.

Which jazz records did he have?

Well, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Jack Tiesgarden – countless people.

Like a lot of the old swing stuff?

Yeah, which, at that time, was contemporary stuff.

In his autobiography, Keith Richards had a really vivid recollection of browsing Chess Records catalogs and, more broadly, the lengths to which he would go to get ahold of the latest blues and R&B records from the United States. Do you have memories of doing anything similar?

Well, they are the generation of rock musicians who are ten years younger than I am. That’s usually their introduction into blues. But I had a big 78s collection of my own long before that. People don’t realize that there was plenty of blues music on 78s ten years before the time Keith Richards was talking about, so I had lots and lots of blues records!

Were blues records readily available in England then? Or did you have to order them from the United States?

Yeah, sure. You know, just regular releases.

It seems like the broader availability of music brought on by digitalization has relegated it to an afterthought in some ways. Do you think the process of having to go out and get ahold of vinyl LPs made people have to listen closely to, consider, and ultimately respect popular music a little bit more at that time?

I guess so, yeah. I mean, there was not the accessibility there is today, of course. You tended to treasure anything you found.

In the liner notes to A Hard Road, you write, “Blues, in its true form, is a reflection of a man’s life and has to stem from personal experiences good and bad.” In what ways did you really identify with the blues then?

The main thing is that when you listen to the records, you’re obviously aware that singers are thinking about the reflection of their own lives and experiences. So, it’s the reality of it that struck me the most, I suppose.

Were you able to feel in touch with the deeper experiential aspects of the blues – even being over in England?

You know, it’s something that’s recognizable and that’s real.

Did you find that a lot of the prominent black blues musicians you encountered were accepting of British blues?

Oh, yeah! Very much so. I think that when they came to Europe, for all the black musicians, it was a ray of sunshine because there wasn’t any prejudice against them like they had to live with in their own country. So there were much more revered and appreciated, and it was a big thing for them to come to Europe.

That’s interesting. Ultimately, they were seeking acceptance as well.

Yeah, of course.

I had a chance to listen to Bluesbreakers Live, which features the Bluesbreakers with Peter Green, Mick Fleetwood, and John McVie in 1967. Can you talk about how those recordings were made available to you? I’ve heard that a Dutch fan taped the show and recently made it available to you.

Yeah, that’s exactly what happened! I’d heard snippets of what Tom Huissen had, because he vaguely shopping it around about 10 or 15 years ago. But it wasn’t very well organized, or he wasn’t sure of what he wanted to do – they were just like 30-second bits of the opening parts of songs. It just sounded like it was a very good quality recording. When it was a dead end, I didn’t pursue it.

But more recently, he was more ready to share all that stuff with the world. I had his original letter where he said that he had these things, and I found it in my filing cabinet and I just reopened the dialogue between us.

That’s amazing. The recording reflects a pretty unique period for the Bluesbreakers, right? I understand that, as a trio, Green, McVie and Fleetwood only backed you for a few months.

Yeah. Peter [Green] had been with me for a year, and John McVie had been with me for going on four to five years. So it was just the addition of Mick Fleetwood that was the short period of time. It’s pretty amazing how it all worked out.

How did Mick come into the band? Did he just audition for you?

I don’t really audition people – I don’t think I ever have. I just know of their work and I make them an offer and they usually don’t refuse, to quote the Godfather. [laughs]

Mick Taylor has always intrigued me because of how good he was, and how anonymous he has remained relative to some of the other musicians you’ve worked with. It’s disappointing that his solo career didn’t get further – his first solo release was great.

He’s a very, very introverted guy. He’s certainly the last person you’d think of who has a sense of business. He’s generally never really hit the headlines.

In interviews, he comes across as very pleasant and thoughtful. I do recall Keith Richards describing him as very distant and shy, though. Did those aspects of Mick’s personality inhibit his prospects for a successful solo career?

Yeah, I think so. He’s not the most organized of people, and he just loves to play the guitar, you know? That’s the way I look at it.

Is it true that you started playing with Mick when Eric Clapton didn’t show up for a gig, and Mick ended up playing Clapton’s parts – on Clapton’s guitar – and then signed on with your band?

Yeah – yeah. Well, he popped up out of the audience that night when Eric didn’t show up. He’d been following the band, and so he kind of knew lots of the numbers. But he disappeared after that gig, and then Eric, of course, came back the next night. I didn’t hear from him again until much later and I remembered who he was.

Was he more or less just a fan at that point?

Yeah, yeah.

So Mick Taylor basically came out of the audience as a virtual unknown, got on stage, and played all of Clapton’s parts?

Yep. That’s it.

That’s unbelievable.

[Laughs]

I know he’ll still sit in and play with you from time to time. After playing with him for such a long period of time, what stands out to you about Mick? What makes him special as a guitarist and a musician relative to others you’ve worked with?

Well, you can’t describe music and what it actually is. I mean, he’s just got an individual style that’s recognizable and he’s got a lot of jazz influences because he’s a jazz fan as well as a blues fan. So it all gets integrated into his playing, just like anyone else who picks up bits and pieces and develops it into their own style.

Mick’s phrasing has always stood out to me. He never overplays and can always adapt his style to suit the music, whether he’s playing with you, the Stones, or someone like Bob Dylan.

Yeah. I think all good musicians know how to fit in because they feel the music.

In an interview, Mick mentioned a 1967 Bluesbreakers performance in San Francisco with Jimi Hendrix and Albert King. It must’ve been a smoking show! Can you remember when you first saw Hendrix play?

Well, when he first came over to England. That was the start of his career. You know, the Fillmore thing was much later. So, by then, Jimi was very well-known on the club circuit in England. Then he made his mark in America.

Can you remember the first time that you saw him perform?

Not specifically, but it was beyond impressive. It was beyond what we had seen before – that kind of showmanship. So it was quite a revelation. I think it affected the British guitar players a lot more than it affected me, with it being their instrument thrown around and let free.

Were there were peers of yours who weren’t totally sold on Hendrix at the time? Or was his acclaim pretty universal then?

Well, I was definitely an instant fan. I didn’t underestimate him – I wasn’t in competition. We did quite a lot of shows on the same bill, and he sat in with us a few times.

Can you remember what he was like as a person?

He was a very shy person, really. He wasn’t bragging about his talent or anything. He was kind of a modest sort of guy who just loved to play.

You’re very well-known, but often in the context of your association with Clapton, Taylor, Fleetwood Mac, and Cream. Has that ever been frustrating or a source of conflict for you?

Not really! It’s all part of my background.

Have there been times that you’ve wanted or felt deserving of strictly independent recognition?

Well, you can’t have control over those things. I’ve always appreciated the fact that people like what I do, and that I have more freedom than anyone else. It’s a winning situation.

How would you like your career to be remembered?

Just as an innovator and a great bandleader.

You’re 81 years-old, you’ve released around 60 albums over the course of your career, and even now, you’re touring pretty relentlessly – over 100 dates a year, correct?

Yeah. It’s really more like 100. Last year, it was 130. This year, it’s probably going to be about 90-something. But 100 is about average, and we get around to all parts of the world. It’s a great life!

That’s amazing. How have you kept the blues fresh, original, and engaging for yourself over such a long period of time? Which aspects of the blues are really timeless to you?

Well, it’s the reality of the blues. It’s how you express yourself, so you don’t really analyze it too much. It comes natural to sing about about real life, and giving it your best shot.

Will you ever play with form or take broader creative liberties to enliven the blues idiom? Or do you focus more on songwriting than compositional devices and feel content playing within a traditional 12-bar structure?

You know, I don’t know very much about how to play anything else, because I just use the blues to express whatever feelings I want to get out. I’d say it’s hard to analyze, but I certainly have more freedom than most main bands, because we do a different show every night and a different repertoire. We’ve got many songs to choose from, and I don’t like to play the same songs every night, so in the course of four or five days there are five completely different shows. All the famous bands have to play the same stuff every night, which would the downside of it for me. I couldn’t possibly think about doing that. We have total freedom and have a great time playing music.

Will you play with a setlist? Or will you call out songs on stage?

I try to make a setlist every night, which is very carefully done to make sure that there’s no two songs in the same key, the same feel or the same tempo. So I put together something that’s going to be an interesting show.

Would you describe yourself as a bandleader who maintains a clear idea of what he wants? Or will you just let your perform at will within the broader framework of a song?

Yeah, the reason I pick musicians is for what they bring to the table, so they make their contribution. You know, you’ve got the right people you’ve chosen, and we have a great time creating music together. We play together all the time and it just falls into place very easily because we all speak the same language.

And you trust that?

Absolutely!